|

Small though gems are, I aver that they conquer the ages. |

|

S. Reinach

|

p. 51 The antique cameo has become a symbol of elegance and beauty. It is often considered among those works of art which emphasize perfection of form and celebrate human beauty, graphically displaying refined gracefulness and miniaturization. Antique cameos can justly be counted a model of this kind of art. They were born of the classical art of antiquity, an art which poeticized and proclaimed as aesthetically pleasing all that was best and most worthy in the ideal of harmonious and perfect man.

The word cameo is generally used to describe carved stones with an image executed in relief (as distinct from intaglios, stones with an incised image, used as seals from time immemorial). The origin of the term cameo is not clear. It is most likely that the word camaheu or camaieul, appearing in French in the thirteenth century and corresponding to the Greek κειμήλιον, was brought from the East by the Crusaders.

p. 52 By the fourth century B.C. the masters of ancient glyptics, the art of carving on stone, were producing not only seals and intaglios, but also scarabs, lions and sphinxes carved in relief from single-colour minerals. But cameos themselves — multicoloured gems cut in relief, most frequently from sardonyx, a special type of multi-layered agate, — only began to appear at the end of the fourth and at the beginning of the third centuries B.C. The introduction of polychromy distinguished the new method of stone-carving from the old traditional forms. By exploiting the different colour layers of the sardonyx, these masters could achieve the kind of colour effects found in painting. The relief of the cameos was emphasized by the play of bright tones and their nuances, from black, through various shades of brown, to blue-grey and white. By varying the thickness of the agate’s white layer so that a dark lower layer could be seen through it, a master was able to create the illusion of modelling in light and shade. The craftsmen chose either Indian sardonyx, which combined white and yellow with warm red-browns, or Arabian sardonyx in which cold blues and blacks, as a rule, predominated.

The birthplace of the cameo is considered to be Alexandria, the town founded by Alexander the Great on the mouth of the Nile in 332 B.C. It is from here that the earliest known and most famous gems originated: the large cameos with the portraits of Ptolemy II and Arsinoë, now in Leningrad and Vienna, the famous “Farnese Cup” in Naples, the “Cup of p. 53 Ptolemy” in Paris. All of these were made by Greek masters at, the Alexandrian court of the Ptolemies.

Following on the campaigns of Alexander the Great, a stream of new, unexpectedly bright multi-coloured minerals flowed from the Orient, bringing about the creation of a new kind of gem. While humble intaglios were used for seals, the cameo most frequently became an object of luxury. Multicoloured gems from precious eastern minerals were mounted in rings, crowns and diadems. They adorned the garments of kings, priests and nobles. Carved stones began to be used to decorate valuable dishes, caskets, furniture, musical instruments. Vessels of crystal, chalcedony and onyx with images skilfully executed in relief on the body became particularly famous.

The refined artistic sensibility apparent in articles made by Greek craftsmen for powerful monarchs and nobles is truly striking. They combine the colourfulness of exotic oriental minerals with the high genius of Hellas.

The Hellenistic kings used to patronize the masters of glyptics. Alexander the Great had his own court craftsman, Pyrgoteles. Only he was allowed to produce portraits of the King on the gems. The collection of carved stones, the daktylotheke, of King Mithridates VI Eupator, of Pontus, enjoyed widespread fame.

The art of carving cameos demanded from the craftsman an extraordinary degree of skill and perseverance. Almost every ancient cameo is an example of a selfless and fanatical love for the beautiful. The same simple tools which were used for p. 54 intaglio seals were also employed for cameos. A bow-drill, and later a wheel with a driving belt rotated varying configurations of cutters. Agate, like most minerals utilized in glyptics, is harder than metal, and therefore the stone was not directly cut by a metal edge, but with the help of abrasives, “Naxos stone”, powdered corundum or diamond dust. The image grew slowly. The master was forced to work almost blind, since the powder of the abrasive, mixed with oil or water, completely covered the design. A craftsman could spend months and even years on the creation of a single cameo. E. Babelon, the French scholar of the early twentieth century and one of the most eminent connoisseurs of glyptics, remarked that it took as long to make a large cameo as to build a whole cathedral.

The hardness of the stone was not the only technical difficulty encountered. It was also essential to determine in advance the sequence of the layers in the agate, which did not always run parallel, often changed thickness and bent capriciously. An inaccurate estimate meant that a fleck of colour which was inconsistent with the design could spoil the image’s silhouette instead of emphasizing it. In the best cameos these difficulties are overcome with such virtuosity that the stone appears to be malleable, and instantly responsive to the artist’s cutter. The layers of agate seem to have been-arranged by nature so that the white of a profile is accentuated by a dark background, and an ivory forehead crowned with chestnut curls.

p. 55 The cameo’s special position among other genres of applied art was determined by its polychromy. The craftsmen could reproduce in stone many paintings by antique artists. In a collector’s daktylotheke cameos formed a kind of gallery of miniature reproductions. Together with frescoes of Pompeii, these copies of pictures preserved in stone are irreplaceable in the reconstruction of the easel painting of the classical artists, now lost forever. The unusual durability of the material ensured the cameo’s long life. Ancient temples have long lain in ruins, many masterpieces of plastic art survive only in fragments, and the pictures of the Greek painters have disappeared without trace. But ancient cameos remain in such an amazing state of preservation that they might just have left the master’s hands.

The collection of antique cameos in the Hermitage can stand comparison with the world’s celebrated collections, with the possible exceptions of those in Vienna and Paris. The Hermitage’s first gems were acquired by Catherine II from the collection of L. Natter in 1764. But her enthusiasm reached its highest pitch in the eighties and nineties. The collections of de Breteuil, Byres, Slade, Mengs (1780-1782), Lord Beverley (1786), Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orleans (1787), The Duke of Saint Morys, and of J.-B. Casanova, Director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden (1792), were all brought to the banks of the Neva. “Cameo fever” was the name Catherine gave to the passion for collecting which gripped her in these years.

p. 56 In a letter to the well-known representative of the Enlightenment, Frederic-Melchior Grimm, she wrote, “My little collection of carved stones is such that yesterday four men had difficulty in carrying two baskets of jewel cases which contained barely half of the collection. To avoid misunderstanding I should point out that these were the same baskets we use to carry logs in winter”. Access to the collection of “antiques”, as the gems were then called, was considered a very special privilege. “Not more than five or six people have seen it”, Catherine told Baron Grimm.

By the end of Catherine II’s reign, the Hermitage owned more than 10,000 gems. A year before her death she wrote with pride to her trusted correspondent, “All the collections of Europe, compared to ours, are mere childish amusements”.

The collection of carved stones was significantly enlarged in the nineteenth century. In 1814 Josephine, the wife of Napoleon, presented Alexander I with the famous “Gonzaga Cameo”. In the same period a miniature vase of sardonyx was acquired from the collection of Baron A. L. Nicolai, together with cameos belonging to General M. E. Khitrovo and the collections of the Vice-President of the Academy of Fine Arts, G. G. Gagarin, the Russian Ambassador to Vienna, D. P. Tatishchev, Princess E I. Golitsyna and Count L. A. Perovsky. Several items were also obtained from the collections of St. Petersburg connoisseurs A. I. Lebedev and V. I. Miatlev and from the Odessa collector Y. K. Lemmé.

p. 57 At the beginning of the twentieth century the Hermitage purchased part of the collection of the Russian Ambassador to Berlin, P. A. Saburov, and after 1917 the Museum absorbed the nationalized collections of the St. Petersburg gentry, the Shuvalovs, the Yusupovs, the Stroganovs and the Nelidovs. By the middle of the present century the Museum collection had almost doubled in size, and additions are still being made today. Archaeological expeditions from the Hermitage often find antique gems in the South of the Soviet Union. New acquisitions by the Museum have also increased the collection. In 1964 the famous Soviet mineralogist, G. G. Lemlein, presented more than 260 ancient intaglios and cameos to the Hermitage.

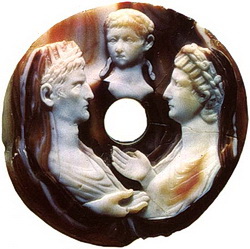

The Museum houses pieces belonging to all periods of the art’s development. Among the greatest treasures is one of the earliest cameos, the famous “Gonzaga Cameo”, sometimes known as the “Cameo of Malmaison”, after the residence of its last owner. The cameo’s history can be traced from 1542, when it was first mentioned in the inventories of the Gonzagas, Dukes of Mantua. In four hundred years it changed owners seven times. In 1630, after the sack of Mantua by Austrian forces, the cameo was brought to the Prague Kremlin, the treasure-house of the Habsburgs. Next it was taken to Stockholm as a trophy of the Swedish troops who seized Prague. When Queen Christina abdicated and retired to an Italian monastery, she took the cameo with her. After her death the cameo found its way into the collection of the Dukes of Odescalchi, but in 1794 p. 58 it was acquired for the Vatican by Pope Pius VI. Napoleon, having seized Rome, took the cameo to the North once more, this time to France, where it remained until the summer of 1814, when the wife of the overthrown Napoleon presented it to Emperor Alexander I.

The “Gonzaga Cameo” was produced in Alexandria by an unknown master in the third century B.C. The rulers of Hellenistic Egypt, Ptolemy II and his wife Arsinoë, are represented here as gods of the Greek Pantheon — θεοί ἄδελφοι. When depicting his patrons the court artist idealized them, attributing to Ptolemy II the youth, beauty and energy of an Alexander the Great. The portrait of his wife seems hieratically severe, the soft features of the face radiate calm. On Ptolemy’s shoulders is the aegis of Zeus, the supreme deity of the Hellenes. Laurel wreaths encircle the heads of the king and queen as a sign of their deification.

The master’s bold technical virtuosity is immediately striking. The energy of form, the soft and subtle moulding, together with a sensitive choice of colour effects, make this cameo a model of the art of “painting in stone”. The profiles of the king and his wife stand out clearly against the ash-grey background. The artist has exploited the fine gradations of the stone’s three basic layers. Behind the dazzling white profile of Ptolemy, picked out as it were by a bright light, the bluish profile of Arsinoë appears receding into shadow. The helmet, hair and aegis of the king are carved from the upper, brown p. 59 layer, while brighter veins are used for the rosette on the helmet, and for the heads of the Medusa and Phobos which decorate the aegis. This strengthens even more the pictorial quality of the cameo. By varying the finish, the master has given a bodily warmth to the middle, somewhat transparent layer, and an almost metallic gleam to the helmet.

In contrast to the cold colour range of ash-greys, blues and violet-browns of Arabian sardonyx, from which the “Gonzaga Cameo” is carved, the bust of Zeus on a cameo of Indian sardonyx is executed in warm tones. In this case the Hellenic artist could work like a painter armed with a rich palette. The head of Zeus, crowned with a wreath of oak leaves, is proudly held high. The profile, the white of which is emphasized by the red-brown curls of the hair and beard, seems to melt into a honey-gold background, while lilac shades accentuate the moulding of the face of the god.

Among the smaller cameos, the portraits of Ptolemy III and Antiochos I are worthy of interest. Each of these kings appears like a new Alexander in their renowned predecessor’s aureole of fame. The queens of the Ptolemies are represented as the goddesses Isis and Aphrodite or as the guardians of the towns of Alexandria and Antioch. The portrait of Cleopatra VII belongs to the end of the Hellenistic era. The bold, succulent carving of the masters of the third and second centuries B.C., so rich in colour effects, was replaced by the cold, rationalistic manner essential to glyptics in the first century B.C.

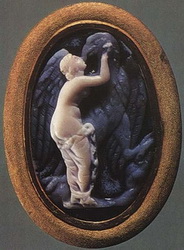

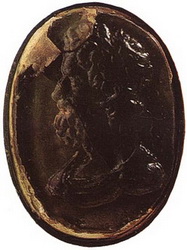

p. 60 Hellenistic cameos on mythological themes are distinguished by their refinement and subtlety. The hedonism of the court determined the characteristics of some artistic genres in this period, which is sometimes compared to the European Rococo. The figures of Horus-Harpokrates or Ganymede and the eagle are elegant and graceful. The choice of themes itself points to the syncretic nature of Alexandrian art, in which the traditional, the Egyptian, peacefully coexisted with the new, the Greek. The representation of Ganymede on a fragment of a large beautiful cameo is apparently taken from some lost painting of the Hellenistic period.

It is probable that this same work inspired the poet Straton:

Haste to the halls of the Gods to heaven, the boy in your talons,

Rise on your wide eagle’s wing, proudly extended in flight.

Speed, so that fair Ganymede may swiftly be lifted to heaven,

To the celestial feast, there to serve wine before Zeus.

Sharp are the claws of the eagle: fear lest you injure the infant;

Do not cause sorrow to Zeus, who for him angrily pines.

|

The carving of this cameo commands attention by its extraordinary softness, and by the scarcely discernible gradations of the relief on the white layer of the sardonyx, in which the body of the boy is carved. The massive, unpolished wings of the eagle emphasize the bodily frailty of Ganymede’s small figure. The skilfully polished Phrygian cap, executed in the dark upper layer, provides the only ebullient element in this strikingly subtle and refined cameo.

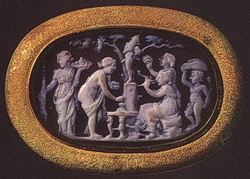

p. 61 The representations of Dionysos in a chariot, of satyrs and maenads and the dances of sileni lead one into the atmosphere of Dionysiac revelry prevalent in Ptolemaic Egypt. In the scenes of sacrifices to Kybele, Dionysos, Pan and Priapos, the spirit of Hellenistic Alexandria is brought to life, with its extravagant theatrical processions, the pomp of the Ptolemies’ court feasts, the merry crowds of townsfolk, whom all this brilliance was intended to blind. The artists’ skill is inimitable. They could inscribe multi-figure compositions inside an oval with dazzling virtuosity, impart an unusual dynamism to these miniature scenes, and reveal the natural rhythm of the design, pleasing when viewed from a distance, like a pattern of lace, but which on closer inspection disclosed a surprising wealth of detail.

The artistic taste of the “antique Rococo” explains the artists’ love for portraying playful cupids, psyches, nymphs and satyrs. Subtle allegories, such as the torments of Psyche torn by passion, are often found. The cameos in the Hermitage showing cupids searing the wings of Psyche with torches, would appear to be illustrations for the verse of Meleager:

If with your fire you would sear, O Eros, her soul without ceasing,

Then, have a care lest she flee — she has the wings to fly, too.

|

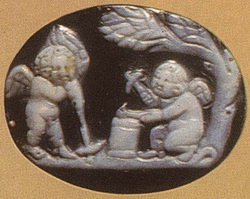

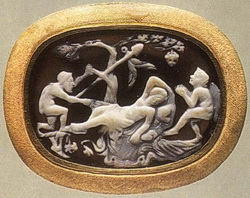

These mischievous little gods of love are often presented in the guise of artisans or ploughmen. With comic self-importance they busy themselves with work, theatrical performances, p. 62 horse-races and athletics. Together with these sentimental allegories and ironic and facetious treatments of ancient mythological themes, the masters of the Hellenistic cameo also produced openly erotic works showing the sleeping Hermaphrodite, Leda in the embraces of Zeus, transfigured into a swan, and various multi-figure bacchanalian scenes.

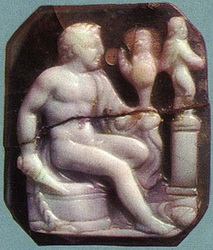

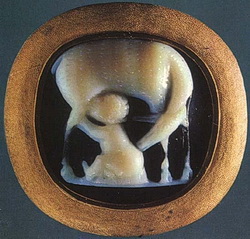

The excesses of town life aroused an interest in the idyllic and in pastoral subjects. The cameo of the baby Telephos, son of Heracles, suckled by a hind, was possibly taken from the famous painting by Apelles. Using only a fragment of the painted composition, the artist manages to turn it into a miniature masterpiece of glyptics. How natural and touching is the movement of the animal as it licks the foundling child, and how skilfully it completes the composition of this small poetic scene! The cameo “Heracles and Omphalë” shows the enamoured captive of the Lydian Queen bathing before he dons woman’s clothing, while a small cupid assists Omphalë. Apparently a now lost picture, “Heracles and Omphalë”, provided the subject both for the Hermitage cameo and the epigram of the Hellenistic poet Philippos:

Where is your lionskin clothing, where your bow, singing with arrows;

Where is the club that you owned, terror of beasts in the wild?

All of them — given to Eros. Nor is there reason to wonder:

He who of Zeus made a swan, Heracles, now owns your arms!

|

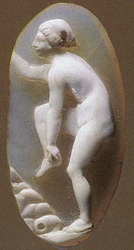

The cameo of Perseus and Andromeda similarly transforms an ancient myth into an idyllic, somewhat theatrical scene. The p. 63 young hero, like a true gallant, shows his capricious lover the fearsome head of the Medusa, reflected in water. The cameo, subtly executed in two tones, is distinguished by its rhythm of line and accuracy of design.

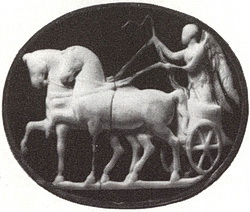

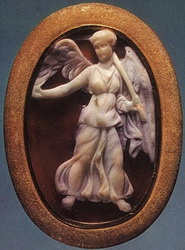

Cameos from this period display other features of Hellenistic art, such as an enthusiasm for heroic themes and passionate images. The Goddess of Victory, the personification of an era of bold and unprecedented campaigns, of grandiose battles and the sudden collapse of states, became a favourite figure in glyptics. Sometimes the winged Nike, standing in her chariot, drives a team of horses, moving as if in time to solemn music. But more often she is shown flying forward and holding a wreath and a palm branch.

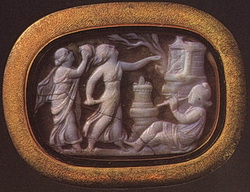

The cameo “The Trial of Orestes” is marked by a restless dynamism reminiscent of the art of Pergamum. Orestes flings himself impetuously towards Athene, who throws into an urn the pebble which will decide his fate. Her arms pressed to her breast, Elektra stands still in anticipation. This miniature scene succeeds in conveying emotions of white-hot intensity. The nervous, expressive style of the carving with its sharp contrasts and restless rhythm strengthens this impression.

The cameos of the Hellenistic period, by virtue of their variety and scope, the unusually wide range of artists, individual styles and the unrivalled audacity of their technical devices, form one of the most interesting chapters in the history of glyptics of the ancient world.

p. 64 Much of Hellenistic culture was embraced by Rome. The example of the monarchs who had been the patrons of glyptics was followed by the magnates of the Roman Republic. Pompey became the owner of Mithridates’ daktylotheke. Of the Roman collections, those of Scaurus, Julius Caesar and Marcellus enjoyed particular fame. The fall of the last Hellenistic power, the kingdom of the Ptolemies (30 B.C.), saw many Greek masters moving to Rome, the new capital of the world. There they placed their talent at the disposal of the Julian-Claudian dynasty. A cameo signed by Rufos, a master with a Latin name, demonstrates the acceptance of Hellenistic traditions by Roman glyptics. Distinguished by exquisite beauty, elegance of design and unusual completeness of modelling, this work reproduces a picture by the Hellenistic painter Nikomachos, “Victory Ascending to the Skies with a Team of Horses”, as it is described by the Roman encyclopaedist Pliny.

The somewhat coarse expressive manner of the Italic cameo artists began to give way from this point to the more spectacular mastery of the representatives of the Hellenic schools. They brought to Rome a whole arsenal of traditional themes Their cameos scarcely differ from the work undertaken for their former patrons. The winged Nike, or Venus and the eagle on cameos of the early Roman Imperial period are indistinguishable from these subjects on Hellenistic stones and coins. Here in Rome they were related to the successes of the Roman armed forces, and to the legends of Venus, the guardian p. 65 of the house of Julii and of all the Romans Sometimes traditional subjects appeared in a new, Roman guise. On one of these cameos, the characters of the ancient Hellenic legends of Demeter and Triptolemos are dressed in Roman costumes. The close relatives of the Emperor Augustus, Germanicus and Agrippina, are shown as the Gods of the Harvest.

Although Roman glyptics long remained in the hands of Greek masters, a new style gradually evolved in these new social and cultural conditions, and under the influence of the traditions of the local Italic art. The cameos of the Augustan period (the end of the first century B.C. to the beginning of the first century A.D.) demonstrate the characteristic rejection of a restless rhythm, purely expressive design, and also of poly-chromy. Artists preferred two-tone reliefs in which white silhouettes stood out clearly on a dark ground. Carving became more and more severe, graphic and almost one-dimensional. Glyptics, like other forms of art in the early Empire, developed along the path of cold rational Augustan classicism.

In their search for themes Roman masters turned more and more frequently to Greek classical art of the fifth century B.C. They derived inspiration from the ideally exalted art of Phidias and Polycletos. As sober rationalists analysing the calm, harmonious beauty of ancient Greek monuments and constantly copying them, they often followed not the spirit, but the letter of that high, ideal style. In this way a number of brilliant, but soulless works were produced, such p. 66 as the cameo of the youth with a horse, reminiscent of the horsemen’s figures on Phidias’ friezes of the Parthenon, or the cameo “Priam and Achilles”.

Just as Alexander the Great had his own court artist, Pyrgoteles, Augustus retained his own personal portraitist, the Greek Dioskourides. Dioskourides was the founder of a whole school of cameo-artists who produced gems for almost a century in the workshop of the Julian-Claudian court. Roman glyptics are indebted to this school for their flowering in the early years of the Empire. Among the portrait-cameos it is possible to find such purely propaganda works as the cameo in honour of the victory at Actium. Here the portrait of the young Octavian is swamped by a sea of symbols of the victory which brought autocracy to Republican Rome. For the masters of classicism it became obligatory to idealize the appearance of the princeps and his familiars. Even in old age, Augustus was portrayed in the aureole of strength and beauty, as if time were impotent before him. Ovid writes of his eternal youth:

Just as the laurel grows greenly, ever one foliage keeping,

So will he, also, retain ever his beauty the same.

|

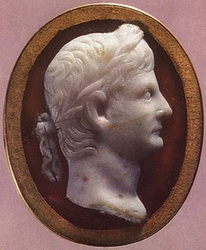

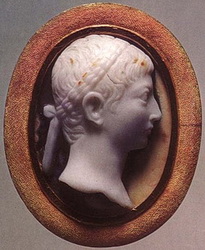

The sons and pupils of Dioskourides produced many cameos with the portraits of Augustus and his retinue. The participants in the cruel dynastic war which split the ruling Julian-Claudian house for nearly a century, are ennobled in their portraits; their youthful, sternly aristocratic faces breathe strength and serenity. p. 67 To search these portraits of Livia, Tiberius, Germanicus and Agrippina for any reflection of their tragic fate, so dramatically related by Tacitus and Suetonius, is to search in vain.

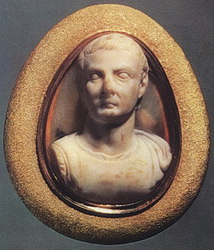

Although confined to the framework of official themes and a unity of style, the court artists were able, however, to retain their own individual characteristics. The portraits of Livia, carved by the master Hyllas, reveal him to be a strict classicist. The polished surfaces with the minimum of moulding and the portraits predominantly in profile show that his main concern is with the silhouette. Eutychos’ portraits of Tiberius and Germanicus can be recognized by a certain mannered quality. One of his more successful works is a cameo of the young Germanicus, where the subtle and painstaking intricacy of the carving by this master-miniaturist emphasizes the morbidly delicate beauty of the youth. The cameo with a portrait of the Nero Caesar is remarkable for its pictorial effect. Epitynchanos’ portrait of Drusus attracts the eye by its severe, but unexpectedly acute design. This cameo discovered in Kerch, is possibly the most accurate likeness in the Hermitage’s wide collection of portraits of the Julian-Claudian house. It seems to revive the traditions of the Italic realism of the Republican period. The master has not overlooked the misshapen skull of the son of the Emperor Tiberius, his cruel, rapacious profile, the evil smile of his twisted lips.

Copies of the best cameos, moulded from glass as medallion-phaleras were widespread throughout the Empire. Most p. 68 frequently, these were numerous portraits of Tiberius, Germanicus and Drusus, but sometimes mythological figures such as the Goddess Roma, the Medusa and the now almost legendary Alexander the Great are also found.

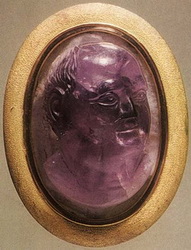

Unlike the work of the Augustan classicists, the cameos of the Flavian period (the end of the first century) once again displayed certain characteristics of Hellenistic art, such as a softness of moulding and an abundance of colour. The portrait of Vespasian, carved in transparent violet amethyst, is executed in this vivid pictorial, so-called “Flavian” style. It emphasizes the coarse bloated features which aroused mockery, of this soldier-Emperor. In the cameo portrait of Julia, granddaughter of Vespasian, the artist seeks to dispel the monotony of the two-toned Augustan gems preferring multi-coloured glass.

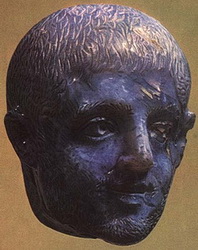

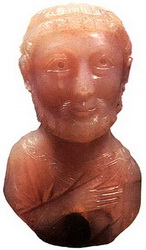

A new wave of classicism engulfed Roman art during the reign of the house of Antonini (the second century). The portraits of Faustina, wife of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, of his daughter Lucilla, and son Commodus, are coldly mannered and severely drawn. Only a love of the brilliant effects of poly-chromy distinguishes these cameos from the work of the classical school of Dioskourides. Polychromy in cameos, and a preference for emphasizing concentrated spots of colour rather than design, together with the soft, “painted” quality of the silhouette, grew more marked in the work of artists of the late Empire. Cameo portraits of the third century, even those displaying clear “barbarisms” of style, are strikingly expressive. One p. 69 example of this is the portrait of Caracalla, another the miniature sculpted head of Severus Alexander. Even at the time of the destruction of ancient culture, artists were still creating genuine masterpieces. The bust of Julian, carved in chalcedony, continues the best traditions of the ancient craftsmen.

In the age of religious fanaticism which saw the destruction of ancient temples and the statues of the “pagan idols”, antique cameos found an unexpected refuge in mediaeval monasteries and cathedrals. Beautiful carved stones were used to decorate the magnificent holy objects of the new cult.

Many pagan themes were easily combined with Christian legends: the Goddess of Victory became an angel, Jupiter became John the Evangelist, the Greek Perseus was transformed into the biblical David, etc. Indeed for a long time the Hermitage cameo with the portraits of Antonia and Drusus the Elder was considered to be the decoration of a wedding-ring belonging to Mary and Joseph.

When the mere reinterpretation of a subject became insufficient, cameos were altered, often fundamentally. For example, at the beginning of the nineteenth century the Italian master Benedetto Pistrucci modified the carving of a cameo dedicated to the foundation of Constantinople to such a degree that it appeared to be contemporary.

One of the largest cameos of the first century, bearing the portraits of Livia, Augustus and Nero, has been reworked several times. Not infrequently ancient gems were only p. 70 preserved thanks to such an alteration or reinterpretation of the subject matter.

Cameos are a rich source of information on the spiritual and material culture of the ancient world. But their fundamental value lies in their artistic perfection. Standing comparison with the finest creations of the ancient artistic genius, the applied art of these masters is a figurative hymn in honour of a bright and joyful conception of the world, in honour of Man and his best qualities — his harmonious beauty, clarity of his mind, the valour of a brave spirit.

Most works of glyptics in later ages were adaptations or simply copies of antique gems. Only a very few masters were able to free themselves from the peculiar “hypnotism” of ancient art. In this creative sphere, as in many others, the ancient world reached a height of artistic perfection, which will long remain a desired but unattainable ideal.

|

|

| | p. 71 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS |

| Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy |

M. P. Vaulina, Klassicheskie i ranneellinisticheskie elementy v antichnykh kameyakh Gos. Ermitazha, Trudy Gos. Ermitazha, t. VII, Leningrad, 1962, str. 232 si. (M. P. Vaulina, The Classic and Early Hellenistic Elements in the Antique Cameos of the Hermitage Museum, Papers of the Hermitage Museum, v. VII, Leningrad, 1962, p. 232 ff.) |

| Vystavka portreta |

Gos. Ermitazh. Vystavka portreta, vyp. II. Antichny portret, Leningrad, 1937 (The Hermitage Museum. Exhibition of Portraits, part II. Antique Portraits, Leningrad, 1937) |

| p. 72 Kultura i iskusstvo antichnogo mira |

Gos. Ermitazh. Kultura i iskusstvo antichnogo mira. Putevoditel. Leningrad. 1963 (The Hermitage Museum. Culture and Art of Antiquity. A guide-book, Leningrad, 1963) |

| Maksimova, Reznye kamni |

M. I. Maksimova, Antichnye reznye kamni Ermitazha. Putevoditel po vystavke, Leningrad, 1926 (M. I. Maksimova, Antique Carved Stones in the Hermitage Museum. A guide-book, Leningrad, 1926) |

| OAK |

Otchot imp. Arkheologicheskoy Komissii (Reports of the Imperial Archaeological Commission) |

| Stefani, Putevoditel |

L. Stefani, Putevoditel po antichnomu otdeleniyu Ermitazha. Zal reznykh kamney, Propilei, t. V, Moskva, 1856, str. 59 si. (L. Stefani, Guide-book to the Department of Antiquity of the Hermitage Museum. Carved Stones Room, Propylaei, v. V, Moscow, 1856, p. 59 ff.) |

| Arch. Anz. |

Archäologischer Anzeiger. Beiblatt zum Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Berlin |

| p. 73 Babelon, Catalogue |

E. Babelon, Catalogue des camées antiques et modernes de la Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1897 |

| Furtwängler, Beschreibung |

A. Furtwängler, Beschreibung der geschnittenen Steine im Antiquarium, Berlin, 1896 |

| Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen |

A. Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen. Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst im klassischen Altertum, I-III, Leipzig, 1900 |

| JDI |

Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Berlin |

| Maffei, Gemmae |

P. Maffei, Gemmae antiquae figuratae, III, Roma, 1708 |

| Miliotti, Description |

A. Miliotti, Description d’une collection de pierres gravées qui se trouvent au Cabinet Impérial de St. — Pétersbourg, I, Vienne, 1803 |

| Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. |

Proceedings of American Philological Society |

| RA |

Revue archéologique |

| Reinach, Pierres gravées |

S. Reinach, Pierres gravées des collections Marlborough et d’Orléans, Paris, 1895 |

| p. 74 Richter, Catalogue |

G. Richter, Catalogue of Engraved Gems Greek, Etruscan and Roman, Roma, 1956 |

| RM |

Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung, Berlin |

| Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst |

M. L. Vollenweider, Die Steinschneidekunst und ihre Künstler in spätrepublikanischer und ausgusteischer Zeit, Baden-Baden, 1966 |

| Walters, Catalogue |

H. Walters, Catalogue of the Engraved Gems and Cameos in the British Museum, London, 1926 |

|

| CATALOGUE |

|

1. |

Ptolemy II and Arsinoë (the “Gonzaga Cameo”). 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. 15.7 x 11.8 cm. Entered the Museum from the Josephine de Beauharnais collection in 1814. Before 1630 belonged to the Gonzagas, Dukes of Mantua. From 1630 to 1648 was housed in the Habsburg treasury in Prague Kremlin. From 1648 to 1689 owned by the Swedish Queen Christina. In 1689 found its way into the collection of the Dukes of Odescalchi; in 1794 was acquired for the Vatican by Pope Pius VI. In 1798 the cameo was brought to France. Inventory No Ж 291.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 72; N. E. Makarenko, Khudozhestvennye sokrovishcha Ermitazha, Petrograd, 1916, str. 240, ris. 87; M. I. Maksimova, Kameya Gonzaga, Leningrad, 1924; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 94, tabl. IV; Vystavka portreta, str. 21; E. Babelon, La gravure en pierres fines: camées et intailles, Paris, 1894, p. 135, fig. 104; p. 76 Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LIII, 2; G. Rodenwaldt, Kunst der Antike, Propyläen-Kunstgeschichte, III, Berlin, 1944, Abb. 422; M. Bieber, The Portraits of Alexander the Great, Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc., 93, 1949, p. 390, fig. 3; W. Kaiser, Ein Meister der Glyptik aus Umkreis Alexanders des Großen, JDI, 77, 1962, S. 227, Abb. 7; G. Richter, The Engraved Gems of the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans, I, London, 1968, p. 155, Nr 611. |

|

2. |

Ptolemy III (?). 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.6 x 1.9 cm — Inventory No Ж 306.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Vystavka portreta, str. 21. |

|

3. |

Antiochos I (?). 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.6 x 1.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 285.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Vystavka portreta, str. 21. |

|

4. |

The Medusa. 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. Diam. 5.3 cm. Inventory No Ж 290.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 67; OAK za 1881, str. 78, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, III, S. 158, Abb. 111. |

|

5. |

Zeus. 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. Diam. 6.1 cm. Entered the Museum from the Princess E. I. Golitsyna collection in 1850. Inventory No Ж 292.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 74; OAK za 1881, str. 77, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, III, S. 158, Abb. 112; p. 77 G. Lippold, Gemmen und Kameen des Altertums und der Neuzeit, Stuttgart, 1922, Taf. III. |

|

6. |

Berenike II (?) as Isis. 3rd century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.3 x 1.4 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 310.

For analogies, see: 1) Tbilisi, Art Museum of Georgia, — A. Amiranachvili, Un camée antique à Tiflis, RA, 33, 1931, p. 41 et suiv.; 2) Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 231, pl. 22.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Vystavka portreta, str. 21; RA, 33, 1931, p. 42. |

|

7. |

Queen of the Ptolemies — protectress of Alexandria. 3rd — 2nd centuries B.C. Sardonyx. 2.8 x 1.9 cm. Reworked in the eighteenth century. Inventory No Ж 155. |

|

8. |

Cleopatra VII (?). Late 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.8 x 2.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 152. |

|

9. |

The goddess Hathor. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.4 x 1.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 243.

For analogies, see: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 138, pl. 20. Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96. |

|

10. |

Selene. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.8 x 1.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 319. Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96. |

|

11. |

Cupid with a butterfly. 2nd century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.7 x 2.5 cm. Entered the Museum in 1855. Found during the excavations of the Artiukhovsky Barrow (Taman). Inventory No APT 55.

p. 78 Literature: OAK za 1880, tabl. III; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, III, S. 152, Abb. 106. |

|

12. |

Horus-Harpokrates. 1st cenlury B.C. Sardonyx. 2.5 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 295.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 134, pl. 123. |

|

13. |

The Rape of Ganymede. Fragment of the cameo. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 3.3 x 3 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 299.

For analogies, see: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 6, pl. 1.

Literature: OAK za 1881, str. 111, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 135, pl. 123. |

|

14. |

Sacrifice to Priapos. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.7 x 2.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 281.

For analogies, see: New York, Metropolitan Museum, — Richter, Catalogue, No 640, pl. 72.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 139, pl. 126. |

|

15. |

Sacrifice to Kybele. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.8 x 2.7 cm. Acquired from the Slade collection in 1780. Inventory No Ж 286.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 64; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95.

p. 79 |

|

16. |

Sacrifice to Pan. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.6 x 2 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 2.

Literature: Maffei, Gemmae, tab. 40. |

|

17. |

Sacrifice. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.2 x 1.8 cm. Inventory No Ж 7.

Literature: Maffei, Gemmae, tab. 81. |

|

18. |

Dionysos. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.1 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the Lord Beverley collection in 1786. Inventory No Ж 277.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

19. |

Nike riding in her chariot. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 3.7 x 4.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 249.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 65; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96. |

|

20. |

Old man with a goat. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.9 x 1.3 cm. Inventory No Ж 315.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99. |

|

21. |

Sacrifice. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 3 x 2.4 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 317.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Miliotti, Description, pl. 65. |

|

22. |

Cupids tormenting Psyche in the presence of Dionysos. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.8 x 2.4 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 316.

Literature: OAK za 1881, str. 112, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Miliotti, Description, pl. 53; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVII, 14.

p. 80 |

|

23. |

Hermaphrodite surrounded by cupids. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 2.1 x 2.6 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 313.

For analogies, see: 1) London, British Museum; Walters, Catalogue, No 3482, pl. 34; 2) Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 48, pl. 7.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 64; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98; Vaulina, Klassischeskie elementy, str. 239, ris. 8; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 135, pl. 124. |

|

24. |

Psyche enslaved by Venus. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.8 x 1.9 cm. Inventory No Ж 288.

For analogies, see: Berlin, Staatliche Museen; Furtwängler, Beschreibung, Nr 11172.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 71; OAK za 1877, str. 205; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95. |

|

25. |

Apollo and Artemis. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.4 x 2.2 cm. Acquired from the Byres collection in 1782. Inventory No Ж 297.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96. |

|

26. |

Perseus and Andromeda. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 3.1 x 2.8 cm. Acquired from the Raphael Mengs collection in 1782. Inventory No Ж 297.

For analogies, see: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 45, pl. 7.

Literature: OAK za 1881, str 96, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 236, ris. 5; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVIII, 1; p. 81 L. Curtius, Falsche Kameen, Arch. Anz., 59/60, 1944-45, S. 1, Taf. 18. |

|

27. |

Heracles and Omphalë. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.8 x 2.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 294.

For analogies, see: Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum; F. Eichler, E. Kris, Die Kameen im Kunsthistorischen Museum, Wien, 1927, S. 237, Taf. 83.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 72; OAK za 1881, str. 114, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; J. Spilsbury, A Collection of 50 Prints from Antique Gems, London, 1785, pl. 8. |

|

28. |

Satyr and two cupids. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.9 x 2.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 280.

Literature: Maksimova. Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

29. |

Nike. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 3 x 2 cm. Inventory No Ж 303. |

|

30. |

Cupids in front of a herma watching a cock-fight. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.2 x 1.6 cm. Acquired from the S. O. Veselovsky collection in 1830. Inventory No Ж 252.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

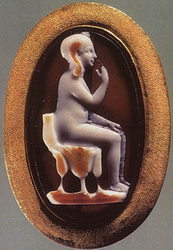

31. |

Youth silting on a rock. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.9 x 1 cm. Inventory No Ж 3. |

|

32. |

Drunken Silenus riding a donkey. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.5 x 1.9 cm. Inventory No Ж 278. |

|

33. |

Cupid with a mask. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.2 x 1.3 cm. Inventory No Ж 251.

For analogies, see: 1) Berlin, Staatliche Museen; Furtwängler, Beschreibung, Taf. 67; 2) Genf, Museum für Kunst p. 82 und Geschichte; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, Taf. 24, 4.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 97. |

|

34. |

Cupid wearing a mask. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.3 x 1 cm. Inventory No Ж 248. |

|

35. |

Diomedes carrying away the Palladium. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 2 x 1.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 13.

For analogies, see: 1) Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 151, 152, pl. 16; 2) Florence, Archaeological. Museum; Reinach, Pierres gravées, pl. 54. |

|

36. |

The trial of Orestes. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.9 x 3.9 cm. Entered the Museum from the A. S. Vlasov collection in 1830. Previously belonged to Count A. G. Razumovsky (before 1771). Inventory No Ж 300.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 71; OAK za 1881, str. 88, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; M. P. Vaulina, O podlinnosti kamei s izobrazheniem suda nad Orestom, Soobshcheniya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, XVII, 1960, str. 61, sl.; Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 240, ris. 10; Kullura i iskusstvo antichnogo mira, str. 162; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVIII, 4; G. Hafner, Judicium Orestis, 113 Winckelmannsprogramm, Berlin, 1958, S. 23, Abb. 6; L. Curtius, Falsche Kameen, Arch. Anz., 59/60, S. 1, Taf. 18; G. Lippold, Antike Gemäldekopien, München, 1951, S. 85. |

|

37. |

Victory ascending to the skies with a team of horses. 1st century B.C. Carved after a Nikomachos’ painting. Signed by the master: ῾Ρουφος ἐποίει (Made by Rufos). Onyx. 1.9 x 2.6 cm. From the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 293.

p. 83 Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 232, ris. 1; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 137, pl. 125; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVII, 6; G. Lippold, Antike Gemäldenkopien, München, 1951, Taf. 15; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, S. 28, Taf. 19. |

|

38. |

Leda and the Swan. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.1 x 2.8 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 305.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 67; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 134, pl. 123. |

|

39. |

Aphrodite with an eagle. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 2.7 x 1.8 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 301.

For analogies, see: 1) Leningrad, Hermitage Museum, Inventory No Ж 21; 2) Den Haag, Münzkabinett; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, Taf. 95, 4.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, S. 83, Taf. 95, 3. |

|

40. |

Hind suckling the infant Telephos. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.9 x 1.8 cm. Inventory No Ж 246.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 66; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 97; Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 238, ris. 7. |

|

41. |

Youth with a horse. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.3 x 2.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 304.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Reinach, p. 84 Pierres gradées, p. 144, pl. 131; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVIII, 11. |

|

42. |

Dionysos riding a chariot drawn by centaurs. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.3 x 3.1 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 282.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 66; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98; Miliotti, Description, pl. 49; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, S. 35, Taf. 23. |

|

43. |

Venus with an eagle. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.8 x 2.4 cm. Acquired from the Saint Morys collection in 1792, Inventory No Ж 21.

For analogies, see: 1) Berlin, Staatliche Museen; Furtwängler, Beschreibung, Nr 11223; 2) Den Haag, Münzkabinett; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, Taf. 95. |

|

44. |

Victory before a trophy. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.3 x 1.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 24. |

|

45. |

Woman by a spring. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 3.2 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 1.

Literature: Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 136, pl. 124. |

|

46. |

Cupid as a ploughman. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.5 x 1.1 cm. Inventory No Ж 250.

For analogies, see: 1) Private collection; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVII, 9; 2) London, Collection of Ionides; J. Boardman, Engraved Gems. The Ionides Collection, London, 1968, No 63.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 97.

p. 85 |

|

47. |

Cupid tying the hands of Psyche. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 2.4 x 1.8 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 20.

Literature: OAK za 1877, str. 204; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99, — Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 137, pl. 124. |

|

48. |

Cupids riding dolphins. 1st century B.C. Onyx. 1.5 x 2.1 cm. Acquired from the Byres collection in 1782. Inventory No Ж 244.

For analogies, see: Florence, Archaeological Museum; Reinach, Pierres gravées, pl. 60.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Maffei, Gemmae, tab. 16. |

|

49. |

Cupid as a horseman. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 0.7 x 1 cm. Inventory No Ж 49.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 64. |

|

50. |

Cupids as blacksmiths. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.1 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the Lord Beverley collection in 1786. Inventory No Ж 41. |

|

51. |

Cupid by a spring. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.5 x 1.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 159. |

|

52. |

Aurora riding in her chariot. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 1 x 1.6 cm. Inventory No Ж 32.

For analogies, see: 1) New York, Metropolitan Museum; Richter, Catalogue, No 624, pl. 69; 2) London, British Museum, — Walters, Catalogue, No 3528, pl. 37.

Literature: Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 234, ris. 3. |

|

53. |

Aurora riding in her chariot. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2.2 x 2.8 cm. Inventory No Ж 11.

p. 86 For analogies, see: New York, Metropolitan Museum, Richter, Catalogue, No 626, pl. 69.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95; Vaulina, Klassicheskie elementy, str. 234, ris. 2. |

|

54. |

Priam and Achilles. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2 x 2.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 26.

Literature: Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVIII, 3; G. Richter, Ancient Italy, Oxford, 1955, p. 70, pl. 224. |

|

55. |

Germanicus and Agrippina as Triptolemos and Demeter. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2.3 x 3 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 296.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96. |

|

56. |

Dionysos, Ariadne and satyr. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Onyx. 1.4 x 1.9 cm. Acquired from the Slade collection in 1780. Inventory No Ж 279.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98.

p. 87 |

|

57. |

Dioskouroi on horseback. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 1.8 x 2.6 cm. Acquired from the Byres collection in 1782. Inventory No Ж 302.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 96; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. LVIII, 12. |

|

58. |

Io, Argus and Hermes (?). 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 1.5 x 2.1 cm. Inventory No Ж 151. |

|

59. |

Sleeping maenad, satyr and cupid. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2.2 x 3.1 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 314.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

60. |

Orpheus. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 1.7 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the A. S. Vlasov collection in 1830. Inventory No Ж 255.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 72; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 97. |

|

61. |

Artemis with a hind. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 1.8 x 1.5 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 242.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni str. 96. |

|

62. |

Dionysos with a panther. 1st century B.C. — 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2.1 x 1.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 312.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

63. |

Artemis. 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.6 x 1.9 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 322.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

64. |

Hera. 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.9 x 2.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 308.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 95. |

|

65. |

Maenad. 1st century. Sardonyx. 3.3 x 2.9 cm. Inventory No Ж 334.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 66; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 98. |

|

66. |

The Medusa. 2nd — 3rd centuries. Sardonyx. Diam. 3.4 cm. Inventory No Ж 145.

For analogies, see: 1) New York, Metropolitan Museum; Richter, Catalogue, No 628, pl. 70; 2) London, British Museum; Walters, Catalogue, No 3549, pl. 37; 3) Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Babelon, Catalogue, N 158, pl. 16.

p. 88 |

|

67. |

Cow. 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 1.3 x 2 cm. Inventory No Ж 123. |

|

68. |

Wild boar and hounds. 1st century. Sardonyx. 1.6 x 1.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 365.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 101. |

|

69. |

Mice and cocks. 1st century. Sardonyx. 1 x 1.9 cm. Inventory No Ж 184.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 101. |

|

70. |

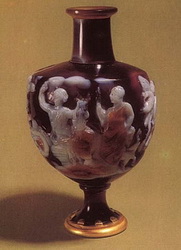

Allegory of the Might of Love. Aphrodite, Apollo, Artemis and Hymen surrounded by cupids. Amphoriskos made of sardonyx. Early 1st century. Height: 5.5 cm. Entered the Museum from the Baron A. L. Nicolai collection c. 1800. Previously belonged to the French Royal collection (from the 17th to the mid-18th century) and to the engraver Jacquet Guay collection (1753-93). Inventory No Ж 361.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 70; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 97; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, III, S. 340, Abb. 190; E. Simon, Die Portlandvase, Mainz, 1957, Taf. 25; H. Bühler, Antike Gefäße aus Chalzedonen, Stuttgart, 1966, Taf. III. |

|

71. |

Allegory of Octavian’s victory at Actium. Portrait of Octavian. Capricorn, kerykeion, shield, dolphin, trident, altar and the hand holding an aplustrum.

Insribed: OCT. CAES. AVG. TER. MA. RQ. VOT. PUB.

Twenties of the 1st century B.C. Sardonyx. 2.5 x 2.4 cm. Acquired c. 1800’s. Inventory No Ж 263.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 29; N. A. Mashkin, Printsipat Avgusta, p. 89 Moskva-Leningrad, 1949, tabl. III; E. V. Fiodorova, Latinskaya epigrafika, Moskva, 1969, str. 298, ris. 75; M. Maximova. Un camée commémoratif de la bataille d’Actium, RA, 1929, p. 64 et suiv. |

|

72. |

Livia. Early 1st century. Onyx. 2.1 x 1.8 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 154.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

73. |

Drusus the Elder and Antonia (?). Late 1st century B.C. Later inscripton: Ἀλφήος συν

Ἀρεθῶνι (Gem of Alpheos and Arethona). Sardonyx. 2.5 x 2.1 cm. The cameo was preserved for a long time in one of the monasteries in the South of France as a Christian relic — the wedding ring of Mary and Joseph. Inventory No Ж 273.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 68; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 31. |

|

74. |

Tiberius. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 3.4 x 2.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 269.

Literature: — Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

75. |

Germanicus. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.4 x 1.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 265.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 143, pl. 129. |

|

76. |

Nero Caesar, son of Germanicus. Twenties of the 1st century. Onyx. 2.5 x 1.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 260.

p. 90 |

|

77. |

Tiberius. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.5 x 2.1 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 266.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

78. |

Agrippina the Younger, daughter of Germanicus. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 4.4 x 3.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 335. |

|

79. |

Agrippina the Elder, wife of Germanicus. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 5.9 x 4.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 343.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

80. |

Livia. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 4 x 3.1 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 267.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Reinach, Pierres gravées, p. 143, pl. 129. |

|

81. |

Germanicus. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.4 x 1.7 cm. Acquired from the Duke of Orleans collection in 1787. Inventory No Ж 261.

For analogies, see: London, British Museum, — Walters, Catalogue, No 3579, pl. 39.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

82. |

Drusus the Younger, son of Tiberius. Twenties of the 1st century. Sardonyx. 2.2 x 1.6 cm. Acquired in 1879. Discovered p. 91 during excavations of the Kerch necropolis. Inventory No П 1879, 24.

For analogies, see: Boston, Museum of Fine Arts; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, Taf. 69, 4.

Literature: N. B. Garshina, Kerchenskaya kameya s portretom Druza Mladshego, Sbornik statey v chest S. A. Zhebeleva, Leningrad, 1926, str. 252 sl; Vystavka portreta, str. 30; M. I. Maksimova, Reznye kamni, Sbornik "Antichnye goroda Severnogo Prichernomorya", I, Moskva-Leningrad, 1955, str. 444, tabl. II; N. Garschina, Eine Kertscher Kamee mit dem Bildnis Drusus des Jüngeren, JDI, 41, 1926, S. 239 ff.; Vollenweider, Steinschneidekunst, S. 77, Taf. 88. |

|

83. |

Tiberius. Early 1st century. Fragment of a blue glass phalera. 3 x 3 cm. Acquired from the Casanova collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 272.

For analogies, see: 1) Rome, Collection of San Giorgi; L. Curtius, Ikongraphische Beiträge, VII, RM, 50, 1935, Taf. 29; 2) Brugg, Vindonissa Museum; A. Alföldi, Römische Porträtmedaillons aus Glas, Urschweiz, XV, 1951, Taf. II-III.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

84. |

Julia, daughter of the Emperor Titus. Late 1st century. Glass paste. 5.6 x 4 cm. Inventory No Ж 344.

For analogies, see: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale; Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen, Taf. XLVIII, 8.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 31.

p. 92 |

|

85. |

Vespasian. Late 1st century. Amethyst. 1.8 x 1.2 cm. Inventory No Ж 337.

For analogies, see: Florence, Archaeological Museum; Reinach, Pierres gravées, pl. 7.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 31. |

|

86. |

Faustina the Younger (?). Late 2nd century. Prase. 3.5 x 2.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 6807.

Literature: W. Stegman, Drei Rundwerke aus Halbedelsteine in der Ermitage, JDI, 1930, S. 4, Abb. 6-8. |

|

87. |

Commodus. Late 2nd century. On the reverse is a cabbalistic inscription with the names of Moses, Joseph, Michael, Shinshiel and Horuel. Sardonyx. 1.8 x 1.6 cm. Inventory No Ж 341. Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 35. |

|

88. |

Lucilla (?). Late 2nd century. Sardonyx. 2.3 x 1.9 cm. Inventory No Ж 329. |

|

89. |

Commodus. Late 2nd century. Sardonyx. 5.3 x 6.1 cm. Acquired from the Saint Morys collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 340.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 35. |

|

90. |

Caracalla. Early 3rd century. Sardonyx. 4.3 x 3.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 345.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 40.

p. 93 |

|

91. |

Severus Alexander. Early 3rd century. Chalcedony. 2.9 x 2.3 cm. Acquired from the P. A. Saburov collection in 1909. Inventory No Ж 348.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 40; W. Stegman, Drei Rundwerke aus Halbedelsteine in der Ermitage, JDI, 1930, S. 6, Abb. 10-15. |

|

92. |

Apollo. 2nd century. Carved after a statue of the sculptor Tymarchidos. Brownish glass. 8.6 x 5.1 cm. Acquired from the Casanova collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 216.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 64; OAK za 1881, str. 80, tabl. V; Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100. |

|

93. |

Septimius Severus. Late 2nd — early 3rd centuries. Brownish glass. 6.3 x 4 cm. Acquired from the Casanova collection in 1792. Inventory No Ж 347.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 100; Vystavka portreta, str. 35. |

|

94. |

Cupid riding a hippocampus. 1st — 2nd centuries. Sardonyx. 1.4 x 1.7 cm. Inventory No Ж 34. |

|

95. |

Warrior with a horse. 1st — 2nd centuries. Sardonyx. 1.5 x 1.8 cm. Inventory No Ж 53. |

|

96. |

The childhood of Dionysos. 2nd — 3rd centuries. Sardonyx. 2 x 2.4 cm. Inventory No Ж 153. |

|

97. |

Fishermen in a boat. 2nd — 3rd centuries. Sardonyx. 0.9 x 1 cm. Inventory No Ж 46. |

|

98. |

Apotheosis of a Roman Emperor. 3rd century. Sardonyx. 1.4 x 1 cm. Inventory No Ж 108. |

|

99. |

Nymph. 3rd century. Sardonyx. 1.3 x 1.5 cm. Inventory No Ж 9.

p. 94 |

|

100. |

Livia. Fragment of the cameo. Late 1st century B.C. — early 1st century A.D. Sardonyx. 2.7 x 2 cm. Reworked in the eighteenth century. Inventory No Ж 262. |

|

101. |

Livia. Early 1st century. Sardonyx. 3.1 x 2.5 cm. Reworked in the eighteenth century. Acquired from the M. E. Khitrovo collection in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Inventory No Ж 268.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30; Kultura i iskusstvo antichnogo mira, str. 161; H. Köhler, Gesammelte Schriften, V, St. Petersburg, 1852, S. 57, Taf. l; J. Aschbach, Livia, Wien, 1864, Taf. III; J. Bernoulli, Römische Ikonographie, II, Stuttgart, 1886, Taf. 27. |

|

102. |

Tiberius. Early 1st century. Onyx. 2.7 x 2.1 cm. Reworked in the sixteenth century. Inventory No Ж 276.

Literature: Maksimova, Reznye kamni, str. 99; Vystavka portreta, str. 30. |

|

103. |

Annius Verus. Sixties of the 2nd century. Chalcedony. Height: 9.6 cm. Reworked in the nineteenth century cm. Acquired from the Stroganovs collection in 1928. Inventory No Ж 364.

For analogies, see: 1) Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, — Babelon, Catalogue, N 198, pl. 32; 2) Paris, Louvre; G. Richter, Catalogue of Greek and Roman Antiquities in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Cambridge, 1956, pl. V; 3) Harvard University; Richter, Catalogue, p. 14, pl. V. |

|

104. |

Augustus, Livia and Nero. Mid-1st century. Sardonyx. Diam. 8.3 cm. Reworked twice in the fifties of the 3rd century and p. 95 during the Renaissance period. Acquired from the Yusupovs collection in 1926. Inventory No Ж 149.

Literature: Vystavka portreta, str. 30; O. Y. Neverov, Rimskaya kameya s tremia portretami, Soobshcheniya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, XXXI, 1970, str. 60 sl. |

|

105. |

Julia Domna. Late 2nd — early 3rd centuries. Sardonyx. 3.3 x 2.9 cm. Inventory No K1471. |

|

106. |

Constantine the Great and the Tyche of Constantinople. Thirties of the 4th century. Sardonyx. 18.5 x 12.2 cm. Reworked in the early nineteenth century by the master Benedetto Pistrucci. Inventory No Ж 146.

Literature: Stefani, Putevoditel, str. 73; M. Maximowa, Der "Trajankameo" der Ermitage, JDI, 1927, S. 299; R. Delbrueck. Spätantike Kaiserporträts, Berlin, 1933, S. 130, Abb. 32; G. Bruns, Staatskameen des 4. Jh., 104. Winckelmanns-programm, Berlin, 1948, S. 29, Abb. 25. |

|

107. |

Julian the Apostate. 4th century. Chalcedony. Height: 9.2 cm. Inventory No Ω 80.

Literature: A. V. Bank, Iskusstvo Vizantii, Moskva-Leningrad, 1960, tabl. 2; V. D. Likhachova, Khaltsedonovy biust Yuliana Otstupnika, Soobshcheniya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, XXII, 1962, str. 18 sl.; P. Leveque, De nouveaux portraits de l’empereur Julien, Latomus, XXII, 1963, p. 74. |

|

|